Notes from the slow lane of healing and change.

I dread the session even before it begins. I am suddenly very very tired. I can feel myself flattening out, wishing I could fast-forward time, anticipating the tedious minutes between me and the end of the hour.

I don’t know where my creative, innovative, somatic therapist self has gone, but she’s definitely not here.

This is what can happen to me when therapy moves so slowly that it seems like nothing is happening.

I know that I’m not alone in having this experience. Indeed, I spent a good portion of a recent consultation group talking with other therapists about feeling this way, and I’ve had many conversations with therapists about it over the years.

It can be hard to know how to respond when clients share the same stories over and over, or help them shift their ingrained protective patterns, or find a way to support them in the misery they feel stuck in. Therapists can feel like they are not making a dent. We can feel exhausted or ineffective or like we don’t know what we’re doing. Sometimes it feels like we’re having the same session over and over and over.

We wonder if we should end therapy with the client, refer them to someone else, or get some more training.

In my case, the good news is that I rarely feel this way anymore. Over the years I’ve come to understand that slow therapy doesn’t mean no therapy. Even when it seems like nothing is happening, that’s almost never the case.

Behind the scenes of slow therapy.

There are many reasons that therapy can move slowly, even to the point where any movement is nearly, if not entirely, imperceptible.

Trauma can keep someone frozen, and the nervous system needs time to learn how to recognize safety.

Shame or fear or self-loathing make vulnerability feel very dangerous.

When the person in front of us has been harmed in relationships, their attachment experiences create a barrier to trust.

Someone who is deeply sensitive or neurodivergent may have a system that metabolizes experience at a different pace.

For clients who have spent a lifetime learning to cage their feelings, opening the door even an inch feels like too much.

Through a parts lens we can appreciate that therapy can only move as fast as the most reluctant or unintegrated aspect of a person. (Thanks Janina Fisher, trauma expert, for that concept!)

We can also remind ourselves that therapy is a unique process and clients don’t necessarily come in knowing “how to do it” or they bring in their own preconceived ideas about it.

Therapy that moves slowly might be therapy that is steady, or protective, or wise.

Even if it feels like watching paint dry.

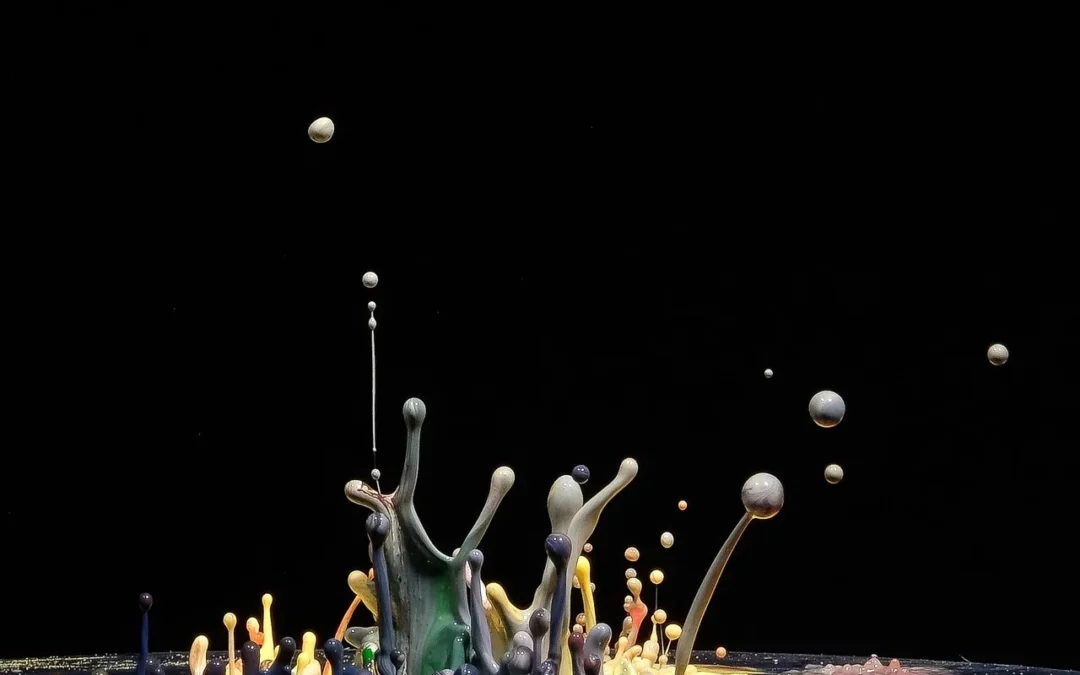

Watching paint dry. Look closer.

I can’t say I have ever deliberately watched paint dry. I imagine it would feel very very tedious – like nothing is happening. But something is happening. You can see this when you’re painting a wall. The color gradually lightens or darkens, patterns form, the texture changes.

When paint is exposed to the air, it goes through physical and chemical changes, such as the solvent evaporating and the pigment hardening. If it’s humid or cold, it will take longer. Too hot and the outer layer might dry too quickly.

Therapy is like exposing a client’s life to air. Something happens. And things change.

Just like with paint, different factors shape the results: the relationship between client and therapist, the material that is exposed, the client’s comfort and capacity to tolerate the process, the client’s coping and regulation skills, the resources that are available to the client, the client’s outside support, the environment the client lives in, and so much more.

For me, when I have a sense that the client is engaged at least a little, when I can notice even teeny changes, when I feel like I have something rather than nothing to work with, I can remain patient and curious. Even if it feels like it’s moving at a snail’s pace, I can get behind it. The process can feel satisfying and useful.

It gets really tricky when there’s no sense of movement at all, and this is when many therapists just feel frustrated, stumped, uninspired, even trapped.

What helps me.

One of the things I have found most helpful in those slow, flat sessions is starting with self-compassion. Recognizing that the experience just doesn’t feel good, being kind to myself, and appreciating that these sessions are an inevitable part of therapy shifts my state. I can listen to my body cues and ask what I need to be more present and open.

I track that I am feeling heavy or that I’m having a hard time paying attention. I notice that I’m leaning forward trying to “make something happen” or that I’ve collapsed with a sense of futility. I realize that I’ve moved “into my head” instead of being aware of my own body, my client, and the space between us.

With renewed mindfulness, I allow myself to settle, ground into my seat or the floor, inhale and lengthen, and exhale more fully. I give myself permission to let go of expectations and become more curious about what is happening — and what is not — and about what my client needs.

Recognizing that my embodied experience may very well reflect that of my client’s, I begin to get a sense of some of what they might be feeling. I can perceive hesitation in their speech, or anxiety bottled up under tense shoulders, or the way that limiting beliefs show up in dismissive gestures or tiny shrugs.

Paradoxically, I remember that it’s valuable to slow down. Slow myself down. Let the process breathe more. That’s it’s useful to introduce pauses and interrupt repetition. I remind myself that it’s valuable to revisit what the client actually wants from therapy, what they find valuable, what they hope for.

Sometimes when we as therapists feel like nothing is happening, clients have a very different experience. They share that we have been extremely helpful to them, that their weekly hour with us is a highlight they look forward to, that they are very grateful for the work we do with them.

Revelations like this reinforce that the relationship between therapist and client is the most fundamental instrument of change. Our presence and our willingness to witness and be a part of the journey is far more important than any of the theories, interventions, or methods we bring to the table.

It is also incredibly useful to remember that most change in therapy is not dramatic. At this point in my career, I firmly believe that slow and small are the best ways to approach therapy. Tiny change plus tiny change, repeated and integrated through the body, is what leads to lasting change and deep transformation.

The value in noticing the tiny, the barely perceptible, the almost nothing.

For transformation to take hold, we often have to identify and name small changes that our clients don’t notice, things we miss ourselves if we aren’t paying very close attention. It can even be valuable to reframe something as a change that might otherwise seem unremarkable.

A slight pause before someone launches back into their story. A deeper exhale, even just a sigh. A slightly softer or more curious tone. A bit of softening of an old defense, or even just a little interest in changing it.

More energy about something a client cares about. A hint of humor when they catch themself repeating something, or even just realizing they are repeating themself. A little feistiness instead of total defeat when feeling frustrated. A whisper of self-compassion.

Almost being on time, or being a few minutes late for the first time ever.

A miniscule amount of anything new, different, or recognized for the first time.

They are all signs of change.

They matter.

And some change shows no outward signs whatsoever. Shifts are happening under the surface, unconsciously, on their own organic timeline.

When we start to investigate the details, the minutia, the cellular level of change, we start to glimpse a whole new world. One of possibility and ingenuity and beauty. It sparks new questions and opens the door to working differently.

So get supervision or consultation, seek out training, make referrals when needed, close a case when it’s appropriate. These actions can be very important, and they can help therapy become more effective or even lead to a breakthrough. But let’s not forget that slow, even exceedingly slow, isn’t necessarily a problem.

Paint will dry as fast as it dries.

Healing and change often happen in the slow lane.

Our job isn’t to make therapy move faster. It’s to be present, to join in the journey, to be curious about how we can help our clients discover their own wisdom and resources. And to trust the process, our clients, and ourselves.

© 2025 Annabelle Coote

This content is intended for informational and educational purposes only. It should not be considered therapeutic, clinical, health, professional practice, business, or legal advice.

Share the Love!

If this was useful, please pass it on to someone else who might enjoy or benefit from it.